Dating back to the 1960s, one can find the initial calls for an Environmental Justice Movement being broadcast by Black activists in the United States who recognized the disproportionate effects that communities of Color face at the hands of climate change. In 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. traveled to Memphis in support of Black sanitation workers on strike, demanding heightened protections against toxicity and higher pay. Like Dr. King, many Black activists have acknowledged how Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC herein) experience climate change and environmental mismanagement in an intensified manner and have always been on the frontlines of the movement for climate justice. While folks in more affluent neighborhoods may have years before they personally face the realities of atrocities such as pollution, lower income communities, which have higher rates of minorities, have already lived with them for decades.

The National Institute of Health reports that in 2018, those experiencing poverty saw 1.35 times more of a burden of chemical emissions than the national average. The situation is even more grave for Black residents who experience on average 1.54 times higher burden than the overall population. One way in which dioxins, or chemicals which severely jeopardize one’s wellness, affect individuals, specifically the Black community, is by impairing their reproductive health. When waste is improperly burned, dioxins are released into the air, which presents a problem especially when this occurs near residential areas. Upon inhalation, those who are able to become pregnant have been found to be more prone to endometriosis, dampened immune and endocrine systems, fetal developmental irregularities, and higher rates of miscarriage and premature labor. If and when these chemicals enter the waterways, residents of the area often endure menstrual irregularities and premature menopause.

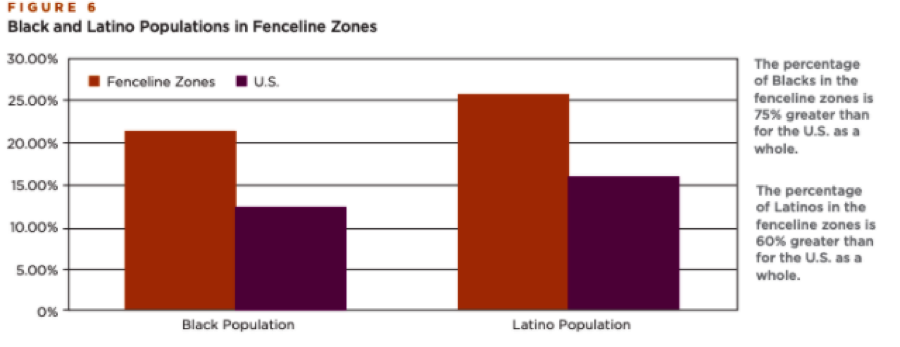

Environmental researchers Jackie Schwartz and Tracey Woodruff suggest that the status quo of assuming chemicals are “harmless until proven otherwise” is dangerous and potentially lethal for communities, especially those with high percentages of Black residents, in Chemical Disaster Vulnerability Zones. The Environmental Protection Agency found in 2014 that Black, Latinx, and low income individuals are disproportionately represented in these zones. The most dangerous regions of these areas, known as the Fenceline Zones, which are the closest 10% of the entire zone to the chemical facilities, see an even greater percentage of Black residents. As shown in the diagram created by the Environmental Justice and Health Alliance for Chemical Policy Reform, the proportion of Black individuals in the Fenceline Zones is 75% greater than the proportion of African Americans in a typical neighborhood in the United States, the housing value is 33% lower than the national average, and the rate of poverty is 50% greater than the national average.

African Americans experiencing financial hardship may be forced to live in these dangerous areas out of economic necessity and a lack of sufficient options in their area, highlighting the need for accessible and affordable housing, among other reforms. The data presented in this piece are just a small fraction of the negative effects that BIPOC face at the hands of environmental mismanagement and ought to highlight the intersections between the climate justice movement with the fight for racial justice. In order to have the same opportunities to thrive, Black communities must be protected against chemical waste, pollution, and any of the threats that climate change presents.

These injustices have not skipped over the Central Florida community. In the 1960s, farm workers in the Lake Apopka area were subjected to pesticides that they believe have caused serious health issues. Similar to the housing issue, Black Floridians in desperate need for work turned to picking crops north of Lake Apopka and have felt repercussions for the rest of their lives. While they harvested, the farmworkers were covered in chemicals dropped by planes, drenching their clothes which they brought back into their homes, exposing their families and babies, which “later had rashes all over their skin,” according to Geraldean Matthew, who worked near the north shore of the lake. After working in the fields, she later developed Lupus and faced kidney failure. Two of her daughters have Lupus as well, which she believes is a result of being exposed to chemicals while pregnant. Countless former farmworkers have either died due to or are currently suffering from similar diseases.

Because of simple necessities such as earning a fair wage to provide for one’s family or to find a home that they can afford, too many Black Americans have been forced to prioritize survival over their physiological well-being. No person should be pressured to make such a choice and change is long overdue.

The greatest way in which to achieve reforms is to elect public servants to office which acknowledge the aforementioned disparities and fight to correct them. One brave individual that speaks truth to power and is never afraid to call out these realities is State Representative Anna V Eskamani of Florida House District 47.

Representative Eskamani has made Environmental Justice a main pillar of her platform and never swayed from her core beliefs that society must change and these disparities must be addressed. The Representative stated that “Florida has a lot to lose if climate change goes unchecked, and one of the most important ways to curb the impact of climate change and to build a more resilient state is through transitioning to 100% renewable energy.”

As the ONLY lawmaker in Tallahassee to receive a 100% pro- environment voting record rating, Anna Eskamani fought for HB- 97, proposing 40% renewable energy by 2030 and full dependence by 2050. While partisan politics led to the bill’s demise, the Representative will never back down from the fight for environmental and racial justice. Because she knows that the constantly increasing global average temperatures and rising sea levels are leading to limited work and housing opportunities and will only continue to worsen, Representative Eskamani has installed environmental justice as one of the pillars of her campaign platform. National organizations recognize Eskamani’s dedication to this issue, as the National Caucus of Environmental Legislators named her as the 2020 Florida state leader and the Sierra Club endorsed her 2020 bid for reelection. She constantly fights to reject urban sprawl, protect our waterways, and ensure that no community is left behind in the fight for a cleaner, healthier environment. Eskamani is unapologetic in her support for the Black Lives Matter movement and recognizes that providing environmental justice is part of the right for racial justice in America.

Representative Eskamani has what it takes to enact structural change in Florida to protect both our vulnerable populations and our environment, but she cannot do it alone. If you would like to support the Representative’s reelection efforts, please visit our website annaforflorida.com and find her on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook to stay in the loop of what’s happening in our community.

To an inclusive, intersectional, incredible future, onward!

Logan Libretti is a 2020 Campaign Intern with Representative Anna V. Eskamani’s team, and a student at the University of Central Florida.

References:

https://www.ejnet.org/ej/twart.pdf

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5844406/

https://comingcleaninc.org/assets/media/images/Reports/Who’s%20in%20Danger%20Report%20FINAL.pdf